Three years ago, I bought a Hamilton Webster wristwatch to restore. I wanted one with which I could control the various aspects of the project. I didn’t look for someone else’s handy work. I kept my eye out for a listing on eBay hoping to find an estate sale item.

Several months passed until someone finally listed a Webster that fit my purchase criteria. After I received the watch, I put it in a drawer where it remained until September 2018. I put together a restoration team and I took delivery from the final contractor in April 2019.

Many people confuse a refresh with a restoration

If you return vintage watches to working condition, don’t take offense to my pointing out the difference between refreshing an item and restoring one. I have refreshed several hundred Hamilton watches since I began collecting in 1983. I just want to make sure that readers have a clear understanding of the difference.

Which brings me to my reasons for writing this article. First I want to share new things I learned while restoring the Webster discussed here and other watches like it . Secondly, I hope to provide serious buyers insights that help them make educated purchase decisions.

I would like people to know that some bloggers represent themselves as restorers while in fact they or he may be a middle man (his own words). He may send his project to a watchmaker who takes photos of a torn down movement to add to a post. That doesn’t make the blog poster a restorer.

A middle man sending a dial to a mid-level quality refinisher doesn’t mean the watch looks as good in person as it does in photos. It also does not mean the guy can put the dial on a movement or set the hands properly. You might wonder if he can even tighten the dial screws.

Oh, and adding an acrylic Germanow-Simon (G-S) lens doesn’t mean the watch comes anywhere close to original. A G-S acrylic lens does not a crystal make. Sure we call them crystals, but calling a watch restored with an acrylic lens lacks authenticity in so many ways.

Then, some of us failed to know the difference in the past. I thought of myself as a restorer for at least a decade before I realized that I fell so short of that designation. Ignorance parallels bliss until we realize the harm we can do.

Yeah. I did not restore antique watches. I also knew that intellectually. When I fixed a difficult movement and reassembled the watch with a refinished dial and added a new crystal, I felt great about the accomplishment. I still needed to spend a couple of years in watch school and at least one or more years as an apprentice.

Sometimes we need a real wake-up call. I didn’t have mine until the day a prototype, once hidden in some boxes at the old Hamilton factory, found me. When my close friend and goldsmith, Luis Garza, wound the undocumented watch, we watched the second hand move around the dial like a new Patek Philippe. It moved smoothly without any hesitation. (I know the difference and I kid you not).

Luis lightly polished the tarnish off the case and we looked on as it ran undeterred like a high-speed train on a bed of air.

None of the watches in my collection compared to that 10K strap watch with a perfect 980 movement. “So, that’s what a new Hamilton would have looked like in a jeweler’s showcase in 1935,” Luis said. “No wonder. We can upgrade some of your watches to look like that. Can you get the movement to perform like this one?”

Maybe, I thought. I could service it, but to make it run like that? We would need the help of one of the four master watchmakers here in Paris, TX.

The Texas Institute of Jewelry and Horology (TIJH) makes its home here. We have some amazing master watchmakers in the vicinity. TIJH brought me to Paris, TX in 2010 as I looked for a watch school in Switzerland. In my search results I noticed that a watch school existed in Paris. Different Paris.

I expressed my concern to Luis about finding original Hamilton parts including dials, hands and crystals. I never had problems finding materials before, but then I always worked on the 14/0 980 series movements. I decided to start looking for parts.

Fortunately, I found an original crystal. I recall how it snapped into the bezel and remained by friction alone. I hadn’t seen that before. No, we did not need epoxy.

I could not source an original dial though. A few sellers offered Webster dials, but no one seemed to have one in a Hamilton package. I had used a dial refinisher in Ohio and gave him a try. I didn’t like the work. Under a loop, the paint ran. I couldn’t see it with my naked eye, but then you have to take a close look at everything when you want to claim you restored a vintage watch.

We tried another dial maker in Atlanta and his work came back impeccable. The difference amazed me. Was it worth another $40? Absolutely. Originally, I wanted a watch that looked like I just bought it from a jeweler in 1932. At least that’s what I thought when we began the project.

Search for a Hamilton Webster on eBay

When I bought the Webster on eBay, the seller represented that it ran and kept time. In watchmaker speak, that means it “ticks”. It does not mean that cleaning, oiling and adjusting will bring the movement back to its original life. It might keep decent time and run longer when you replace the mainspring, but I doubt it will run like new.

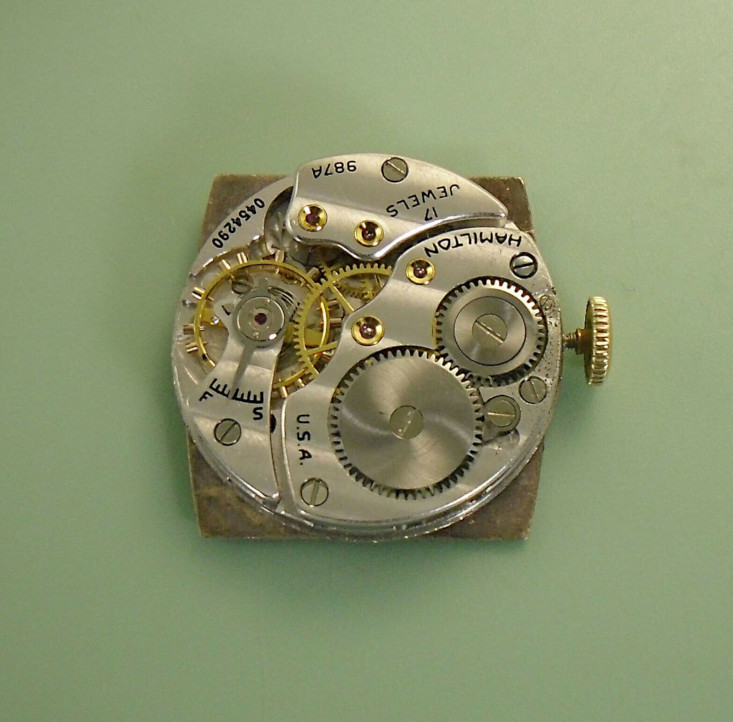

I only know of three consumer vintage Hamilton movements that stand a chance of returning to their original state even with original Hamilton parts. Those include a 992B railroad watch, a 982 14/0 wristwatch movement and a 987A 6/0 wristwatch movement. I can’t speak to the old Hamilton lady’s watch movements. I can say that no other American made watch will perform like those three Hamiltons. None.

Even though the Webster “ticked”, I didn’t know if the movement would ever behave like it did out of the showroom case. I even doubted it could hold itself together even if I rebuilt it with all original Hamilton parts. It still needed a stunning pillar plate.

Hamilton sold the Webster with a 987F movement, which meant it had friction jeweling. While one would consider that a positive compared to the original 987, the 987F still came with steel hairsprings and mainsprings. That meant all kinds of performance problems even after a night out on a date.

I expected to open the Webster and find that model, instead it had a 987E movement. I felt a bid uneasy about that. The 987E came with friction jeweling and the Elinvar alloy hairspring. I could have considered that a plus, but at some point during the previous 85 years, someone switched movements. Also, Hamilton had not perfected the Elinvar alloy in the “E”. That occurred years later.

I had no plans to source a 987F just so that this Webster might appear original. In fact, I changed my mission and went with a strategy Hamilton developed in the late 1930’s.

In 1938, the company released a new 6/0 movement with friction jeweling, extra elinvar alloy hairspring, a motor barrel that adjusted to temperature (to keep the alloy mainspring relevant), a slightly different double roller escapement, a new steel escape wheel, Breguet “E” hairspring, compensating balance and precious metal plating of the heavy pillar plates. Essentially, they created a modern clock that just preceded the famous 992B pocket watch, at the time considered the finest hand wound movement ever made. (Some master watchmakers still consider it the finest ever made).

I decided to source a 987A and use it like I would if I had a failed modern movement to replace. I would simply replace the 987E movement with a 987A and alter my restoration strategy. Instead of making a museum quality Webster, I decided to rebuild the Webster as a vintage Hamilton watch for daily wear. Mine.

I found a 987A and hired one of the master watchmakers in the area to restore the movement. The most accessible master, Ted Tongson, accepted the movement and turned the watch around in two weeks. He replaced any suspect parts with new original Hamilton ones. I couldn’t ask for a better job.

Oh, the Case

The seller of my Webster did an excellent job of photographing the watch so that a buyer couldn’t see the “brassing” along the edges of the back. I paid too much for the watch and I would not expect a seller to have inclinations toward accepting a return after I received it. Perhaps that prompted me to put it in a box and forget about it for two years.

Luis suggested reinforcing the case frame and re-filling the back with the same shade of gold as the rest of the watch. This Wadsworth case had a thin silver layer above the brass on the back below the top layer of gold fill. Looking back, perhaps a goldsmith used silver to fill an engraving.

One of the metallurgists from the jewelry school suggested using nickle on the case back and sides. No one doubted the merit of that if we planned to electroplate the case. Nostalgia prevailed and we only went for reinforcing the stressed areas with more silver.

Now, I needed to make a decision about replacing some gold. Luis soldered spots on the case and reformed them to their original shape. At $35 a shot, the cost rose quickly.

What about the larger real estate? We did not have a fabricating facility like the ones used when Wadsworth made cases. We didn’t have a plating machine (even at the school) capable of laying 20 microns of gold over sterling silver like the registered edition Hamilton watches made in the 1980’s.

I dug in and researched different ways of filling the open area on the back. Luis and Ted also lent their expertise. Finally, no one saw an adequate solution.

How Wadsworth Made the Case

Finding how manufacturers made gold fill cases helped me make some decisions. Wadsworth and their competitors created gold filled cases by sandwiching two layers of gold about 1/2 inch thick on either side of a 3/4 inch layer of brass or brass-alloy. Workers would solder the materials together under high pressure and temperature in ovens.

After cooling the sheet, workers would use rolling mills to create blanks and reach a specified thickness. Craftsmen would use the blanks to make finished cases similar to solid gold ones. Hamilton bought thicker blanks than their competitors.

Final Finish on the Webster Back?

I had to make a financial decision regarding my Webster. Luis had done an excellent job reinforcing the structural integrity of the case and filling the worn areas. How much more money did I want to spend on this Hamilton to make it ascetically pleasing? None.

As you can see in the photo, just left of center and a few degrees north of the crown line, a worn spot remained. Well, it appeared worn. Actually, the gold didn’t match the rest of the case.

When I reflected on the first reason I bought the watch, I recalled wanting to restore it to wear. Finding the undocumented prototype watch pictured above gave me the idea to reach further than I would have under a more studied approached.

In forum posts and in newsletters, many fellow collectors had warned against attempting to repair gold filled watch cases . In previous years, I only sought out unworn or slightly worn solid gold watches for my personal collection. Luis had already beaten the odds when it came to making a better structural case than the original Wadsworth and few people complain about Wadsworth cases.

I capitulated. I had over $700 in the project and what had I learned? Quite a bit.

What did I learn?

- First, I should not recommend doing what I attempted to do. I justified the cost and effort by saying I wanted a watch to wear. Life is shorter than we think and I could have put my time to better use. Would you call this second guessing? I do.

- Trust other collectors’ experience. If we read carefully, we can tell the difference between the voice of knowledgeable commentators and less studied ones. I thought I knew a way around what others said could not happen. Oops.

- Tom, at some point, yeah, stop throwing good money after bad. What would I have done differently? I could have parted out the Webster and bought something else.

- I can always get worse for less.

- Buy a Hamilton Glen Curtiss (if I can find one) instead of a Webster.

- Always warn people to keep an eye out for bloggers who claim to restore watches and who should only write to help others with identification.

- Get more sleep.

That’s not all I learned, but then we never really stop learning if we confess the truth.

Respectfully submitted

If you want to reach Ted Tongson, email him at: TheWatchDoc@mail.com