If you read much about Hamilton’s 992B pocket watch movement, you will see accolades galore among amateur watch enthusiasts primarily on watch forums. You can also find technical comments coming from unpaid dabblers, who seem genuinely authoritative. They just have not gone deep enough into watchmaking to provide information I can use.

In-depth analysis from people who work on watches 10-12 hours a day seem rare. People who can compare a Hamilton wristwatch to the plethora of other brands and models tend to avoid watch forums and meetups. At the end of the day, they just want to clear their bench, eat dinner and do something different like watch TV.

Professionals have told me that Hamilton watches present few problems to them. As one watchmaker told me, the movements typically just need cleaning, oiling and few adjustments. The watchmakers can still find parts for old Hamilton wristwatches from material houses. They consider Hamilton elegant but very straightforward.

No need exists to search the Internet for some esoteric solution to a hairspring issue and so on. They don’t feel the need to answer forum questions or comment about Hamilton movements. Full-time watchmakers stay busy and have solved the same esoteric problems many times.

I chose to talk to a Rolex specialist who also services a multitude of Swiss movements and loves certain Hamilton wristwatches, primarily the 980, 992B, 982 and the 987A.

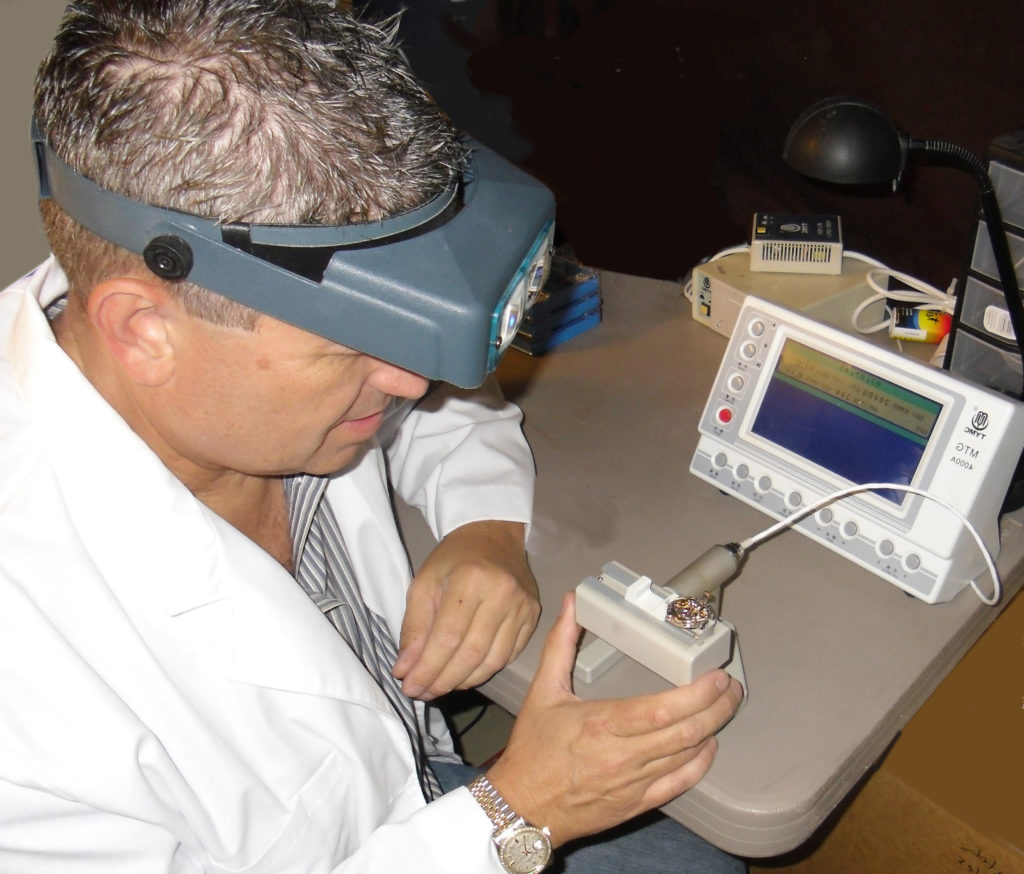

Ted Tongson services about six watches a day, so he has little time to sit and discuss the esoteric differences among watch manufacturers. Jewelry stores make up the bulk of his business, but some Hamilton collectors and vintage watch retailers like me have found him. He charges me about 50% of what jewelers charge, that’s because he charges wholesale prices to those stores who in turn double and triple his prices.

I have worked on many watch movements, but I don’t have the experience of watchmakers who make their living in the trenches day by day just servicing watches one after another. While I have met and worked next to many knowledgeable men and one woman who work in the field, I have only known four masters.

Ted Tongson graduated from the Texas Institute of Jewelry and Horology and has worked as a master watchmaker for two decades. I met Ted at Luis Garza’s jewelry store in Paris. After I had an injury accident, I asked Ted to take over my workload while I recovered. His turn-around time surprised me. He brought me back a 987E movement in less than a week.

After servicing several of my Hamilton watches, we spoke at length about his experience. While accessible, Ted maintains he “is” a private person.

TA: I overheard you say that your grandfather worked as a watchmaker in Seattle. My grandfather also practiced as a watchmaker for his entire working life. Do you think its in our genes?

TT: Not really. I didn’t know my grandfather was a watchmaker until after his death. My grandmother gave me his tools, which surprised me. I spend over ten years as a bench technician in the jewelry industry before I became a watchmaker and neither one of them ever mentioned his business. I don’t know why.

TA: So, you got interested in watches on your own?

TT: I like to tinker with devices of all kinds and have since I can remember. I admired pocket watches, loved the way the parts moved. Their intricacies and precision drew my interest. I wanted to know how they worked.

I managed my jewelry store and staff in San Antonio, attended school four days a week and still don’t remember getting much sleep. All to study under Frank Poye.

TA: OK. Another thing in common. I quit writing IT books and moved here to study at TIJH. After I took his classes, I found out he made watches from scratch. That’s an unusual master watchmaker hidden in a rather small East Texas community.

TT: He’s more of a machinist than me. Many people consider him the “it” guy: the master watchmaker in the US. Swiss trained and after thirty years teaching at the top ranked watch college in the country. He has seen everything. A couple of months ago, I used him to help revive a World War II German navigator’s watch. He made the missing parts from scratch. I don’t know anyone else who could do that. And, he undercharged me.

TA: I read a survey of full-time watchmakers in the US that indicated less than 500 remain active. In 2010, the same survey indicated 1500 existed in the US down from 2500 in 2000. The average age was over 80. The number of new graduates each year in the US averages 10.

I met a middle-age student in my class who worked full-time as a watchmaker in Dallas. During the session on tear-down, cleaning and reassembly, he said that he didn’t disassemble movements. He simply put them in a cleaning machine whole.

TT: We call those guys, dippers. A shortage of well-trained watchmakers has become a reality. In my Guild in Austin, we had about 15 members. Everyone was 70 years or older. Except me. Yeah, I can see a shortage, but jewelers look for watchmakers and many have no ethics much less training.

TA: I wanted to talk about your experience with Hamilton. You say you will work on any watch your customers present. You also propose a two week turn-around but from what I have seen, you turn everything around in a week. Aside from the plethora of watches you see, what’s your specialty?

TT: Rolex. Yeah. Rolex makes up about 80% of my workload. I have four primary accounts and while they send me other high-end watches like Breitling and Panerai, people consider me a Rolex specialist.

TA: You mentioned Hamilton watches as one of your favorites. How do you compare them to other watches?

TT: I believe they made incredible watches if you only take into account the 1930’s and 1940’s. Later on they imported Swiss movements like Certina for automatics.

If you limit the discussion to the 992B, I consider it one of the finest watches ever made. You also have to consider the Marine Chronometer one of if not the most accurate manual timepieces ever made. When stationary it compares in accuracy to the finest electronic movements.

TA: You also gave high marks to the 982 wristwatches you serviced for me.

TT: As far as a hand wound mechanical with no complications, I love it. The 982 can perform as well today as when Hamilton made it and I haven’t seen another movement from that time period that comes close. Customers rarely ask me to make six adjustment on a watch, but I have done that with a 982 and they will perform to Swiss chronometer standards.

TA: Like in the COSC standards.

TT: Exactly.

TA: You’re talking about 80 plus year old movements. What makes that possible?

TT: The materials and manufacturing methods. Hamilton had to meet strict requirements first for the railroad industry, later for the US postal service and finally for the military. The US couldn’t buy maritime chronometers, so they challenged the industry to make one and Hamilton did it. To get there, they had to stop buying mainsprings from the Swiss.

At the time, Hamilton railroad watches used Elinvar hairsprings, but the monthly service requirements for watches used by engineers and conductors exposed vulnerabilities in the balances. The alloy became unstable, damaged easily and in some situations sagged.

TA: How did Hamilton correct the problem?

TT: I can only tell you what I have observed. The 992E railroad watch has a soft hairspring. It takes three times as long to make one stable as the 992B. The material specs I found say that Hamilton invented a new alloy in 1938 (editor’s note: Ni-Span-C) and called it Elinvar Extra. I believe they called it that because of marketing. It doesn’t behave like Elinvar. The 992 became sturdier when Hamilton added the Elinvar Extra alloy to the hairspring.

TA: So, Hamilton reinvented a hairspring alloy and put it in 992B. What about the smaller movements, the 982 in particular?

TT: They didn’t have the same issues as pocket watches. Unless someone damaged one, the 982 balances poise perfectly. But, after 1941, Hamilton used Elinvar Extra in all their 980 and 982 replacement parts. The 982M (Medallion) came with the new alloy hairspring and bi-metallic compensating balances. Those watches run stronger than watches with soft hairsprings.

TA: How much stronger?

TT: Amplitudes of 230-250 for the soft ones and 290-310 for the new ones.

TA: That’s quite a difference.

TT: Right. In some situations, the parts envelopes have dates stamped a year apart. The later ones used the sturdy alloy.

TA: One of the great unanswered questions I see on watch forums deals with the difference between the 980 and 982 calibers. Usually, people ask if upgrading from a 980 to a 982 makes that much of a difference and if so why. What’s your take on that.

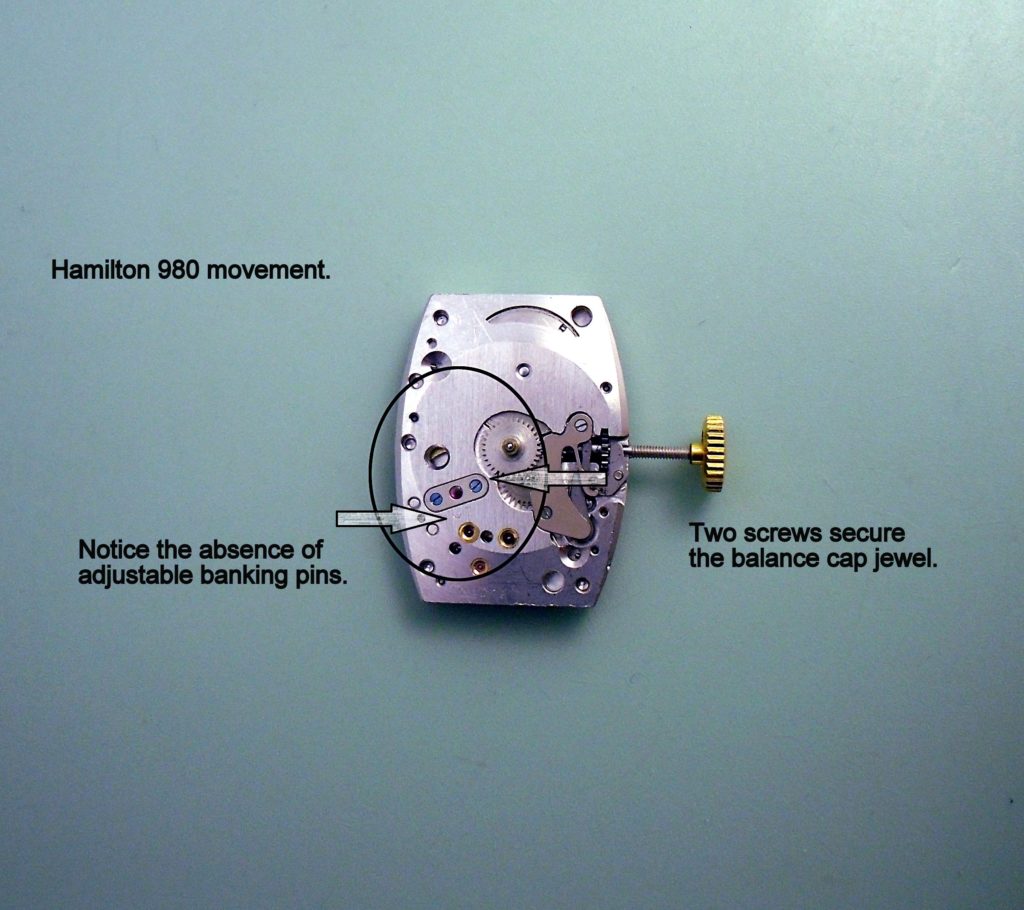

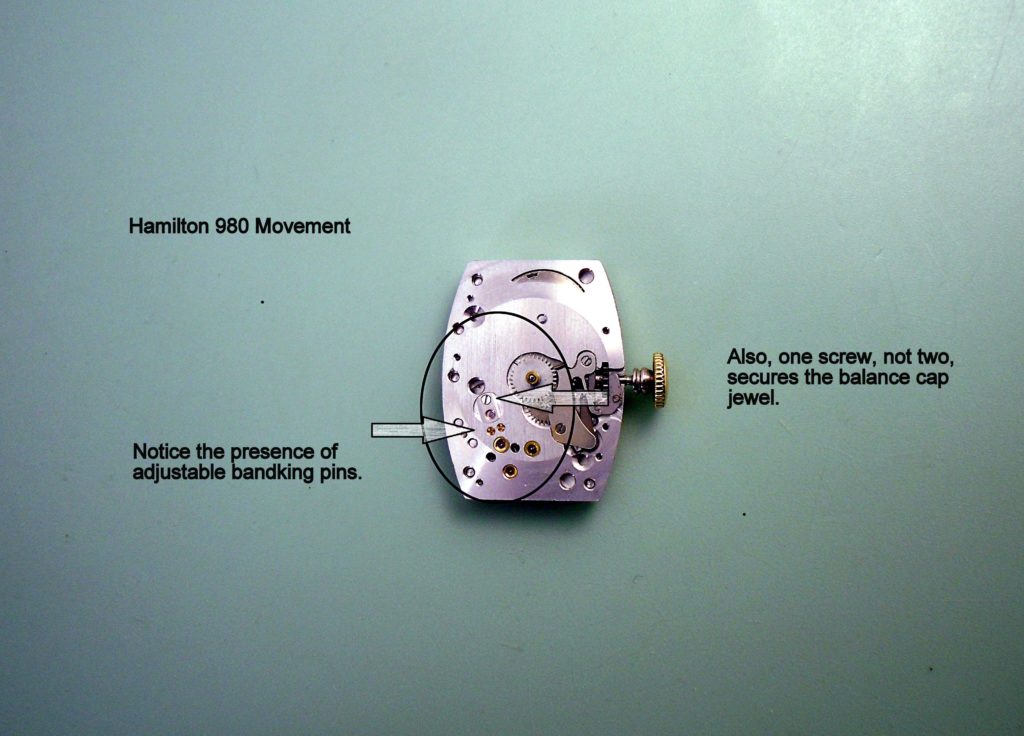

TT: It depends on the 980. Hamilton did not manufacture all 980 models the same. Some significant differences exist between model years. Generally, I would upgrade to the 982.

That said, I have achieved remarkable performance with some 980’s I worked on. Hamilton improved the 980 movement around 1938 and made another upgrade in 1941, which the military likely demanded.

I believe Hamilton dumped their lower grade 980 models on the consumer market after the war broke out. The company had to do something in the consumer market to offset the Swiss.

Some jewelers made their own cases with platinum and solid gold and used 980 movements. Those movements often used the old alloy hairsprings and mainsprings. You have to use a special tool to adjust (poise) the balance instead of a screw driver. Many lacked adjustable banking pins.

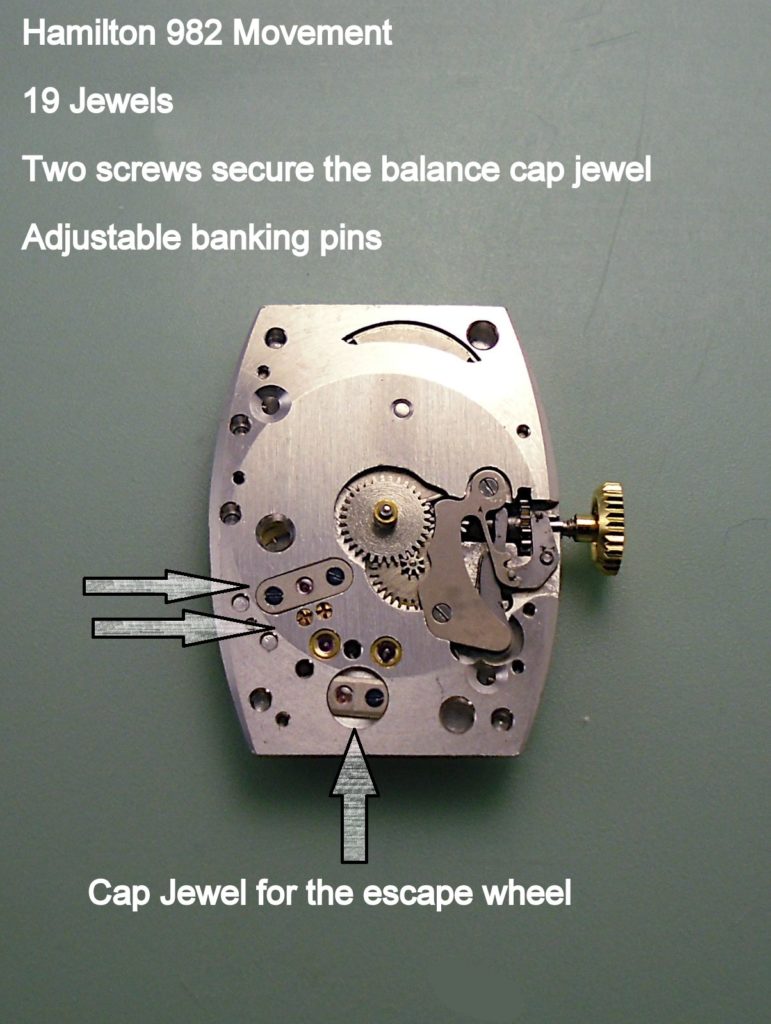

With the 982, I can adjust the jewels and the banking pins easily which helps increase the performance. Do you want me to talk about end-shake and the escapements?

TA: Sure.

TT: The 982 has cap jewels for the escape wheel, both upper and lower. That keeps the oil in place. It keeps the pallet jewels in line and the watch runs smoother and performs much better.

TA: You mentioned something about the pillar plates. Do you consider that a factor?

TT: Yeah. I do. The metal castings look indestructible. I don’t see heavy pillar plates like the ones Hamilton used in the 982 in other companies’ movements. Most American watches made during the era had cheap Swiss parts. Actually, Hamilton made three watches that have much in common – the 982, 992B and the 987A. They plated those movements with nickle and used similar alloys in each watch. That made for watches that could run for more than 100 years if serviced correctly.

TA: What about the escapement and wheels.

TT: They used real sapphires and rubies, not synthetic ones like the Swiss. I oil them and the lubricant stays in the jewel. In other watches, the jewels don’t capture and hold the oil correctly. In the 982, the oil stays in place. The 19 jewels cover the points where I see wear in other watches. If someone hasn’t over tightened the plate screws or scratched something, then the 982 just runs at high amplitudes without much work on my part. Actually, the 982 has the highest I ever see.

TA: I understand that Hamilton also used balance wheels made from an alloy.

TT: Those first showed-up in the pocket watch. I don’t know about the wristwatches in general. More likely than not, Hamilton used them in

the post-1941 movements.

You probably won’t find original Hamilton balance wheels at parts houses today, but I found a few when I purchased parts cabinets from watchmakers’ estates. Some balance wheels have the silver and nickel alloy, no doubt. The timing machine gives me clues and lets me know if a watch has the better parts. I see a higher amplitude.

I would suggest that collectors just refrain from searching for those alloy balance wheels, though. The 982 out performs any wind-up watch I have seen. I still remember the first time I put one on my timing machine and seeing those numbers. I hadn’t even adjusted it yet.

TA: Okay. We already discussed adjustable friction jeweling, so I won’t belabor the end shake or the well known escape works. I do want to understand why you have listed pre-serviced movements. What’s that about?

TT: I usually start a job when I have a customer. A watch comes in from one of my accounts and I start a ticket. You’ve seen how I manage jobs. We all have problems finding vintage watch parts, so when an old movement comes into the shop, I book it and depending on the complaint, I start looking for parts. I also have other customers who collect Hamilton watches. You’re not the only one. I would say most of the collectors also have 992B’s.

TA: The people I talk to collect wristwatches but many tend to own at least one Railway Special.

(Special Note: A fellow Linux guy wrote an extensive article on the 992B. It’s the best collection of information I have seen about that watch.)

Note that the article misstates the origin of the 980-982 movements. They did not come from E. Howard. Hamilton tried to make a few wristwatches with 982 movement. That occurred years after the company purchased the failed E. Howard trademarks. The effort failed to produce sales.

TT: That jives with what I see.

TA: I found the 992B an easy watch to service. Do you agree?

TT: I do. The watch is a breeze, but Hamilton collectors, want me to do extra things. It becomes expensive when people ask me to source hands, dials and crystals. I do it, but it takes about the same amount of time as servicing a movement. You have to know where to get those items. I do, it just takes time.

TA: Is that why you sell complete serviced movements?

TT: Yeah. To make it easy for everyone, I have already serviced movements available. That cuts down on the extra time I would spend. I warranty the work on those movements, but my customers usually ask me to install them. It still takes time to disassemble and reassemble a watch with a pre-serviced movement.

TA: Can you keep a steady inventory? What about parts?

TT: I don’t have any problems getting parts for the 982. I send an order to a material house and they just fill it. Even today, Hamilton parts seem relatively plentiful.

TA: You really like the 982. What about the 980?

TT: If someone wants extreme accuracy and a watch that doesn’t require much service, then they should use a 982. Hamilton used the 980 as a budget movement during the Great Depression. Some of the 980’s don’t have adjustable banking pins, for example. If the balance doesn’t swing correctly, a watchmaker has to manually bend the banking pins in place.

Also, 980’s came in 10K gold cases and amateur watchmakers can buy those watches for less than $50 on eBay. Once they put their hands on a watch, you can bet that they did something to damage the movement. I cannot afford to spend time finding their mistakes, polishing pivots or straightening out a train of wheels.

Sometimes, I buy watches for parts. If the watch comes straight out of an estate, I have a higher level of confidence that no one has messed with the movement. On eBay, I don’t know what to expect.

Earlier this year, I needed a stud screw for a 987E. I bought a watch on eBay and I found only one usable part: the stud screw. The rest of the watch had no usable parts. That’s sad.

TA: Your advice then?

TT: If someone wants to practice, 980’s will let him or her do that. If you have a good case and you want a better watch, find a 982 and make sure it’s serviced or get it serviced.

Many people buy watches that say the “they work”. We call that “ticking”. Eventually, the movement will fail. Old gummy oil and dirt will ruin a movement. You’ve seen the dirt in the cleaning fluid.

TA: I wish everyone could see what comes out of a watch movement when we clean one. Funny, I talk to sellers who say that they don’t get a penny more for a serviced watch than a non-serviced one.

TT: I think that’s true for watches that sell under $250. People that search for vintage Hamilton and vintage Omegas expect to pay over $250 and want the watch serviced or they have them serviced.

Back to the 982 balance. Purists who want a movement and serial number that matches the watch when made, will just have to take their chances. The later the year, then they’re more likely to get the better alloy balance wheel.

TA: What can someone expect to pay to have a vintage watch serviced?

TT: For cleaning, oiling and adjusting – a COA – between $95 and $145 plus parts.

At that price, the watch will keep time. I usually exceed factory specs. If someone wants four, five or six adjustments and less than a second a day accuracy, then they’ll pay more.

TA: Your price seems less expensive than the price list I got from my goldsmith.

TT: Remember, I am officially listed as a wholesale jewelry supplier. The jewelers double and sometimes triple what I charge them. That’s not my concern.

TA: So, can anyone go to you directly?

TT: They can.

TA: Thank you.

TT: You’re quite welcome.

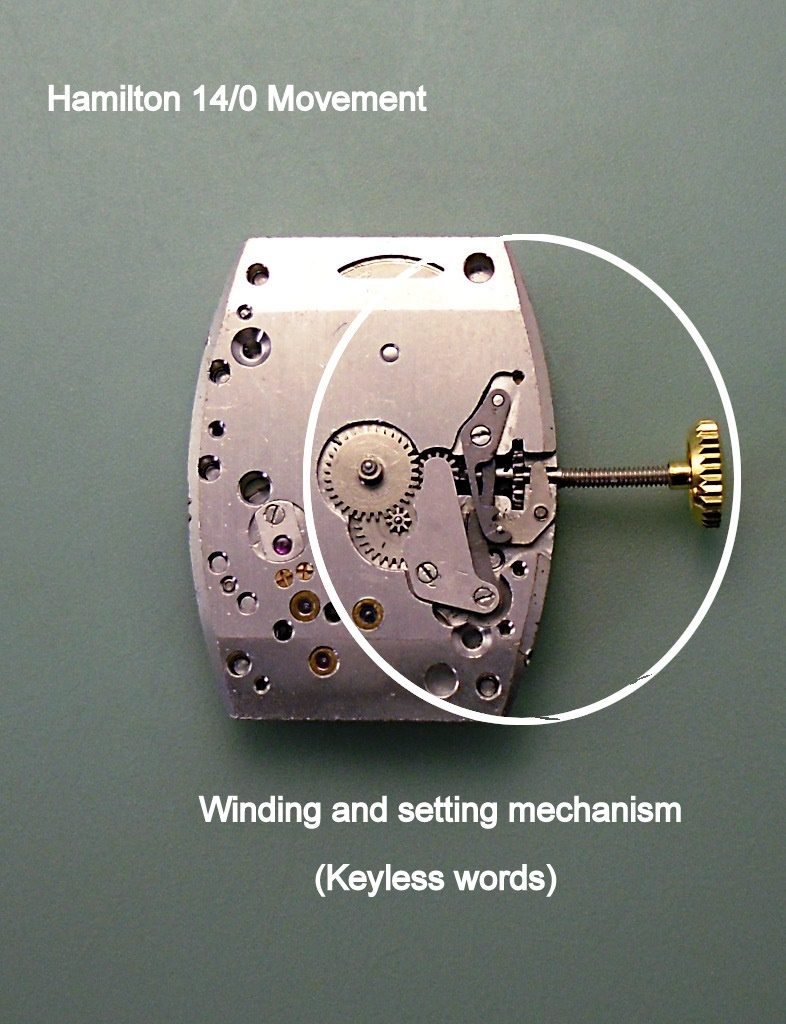

Ted pointed out additional features to consider when choosing a vintage Hamilton wristwatch. We already know most of those with the exception of the winding and setting works.

The winding and setting mechanism of the 980-982 (also known as the keyless works) has no equal. You won’t see another watch movement that comes close to the quality of a Hamilton in that regard.

You can reach Ted by emailing him thewatchdoc@mail.com

Respectfully submitted