Hamilton had a rough 1932. They had to close down the $5 million Illinois Watch Company and move the assets to Lancaster, PA. Management chose to retain the brand name, but Illinois stopped making watches in the depth of the Great American Depression of the 1930’s. Hamilton sustained its only financial loss in 1932.

Watch sales in the U.S. went from over five million to around $800,000 per year during the Great Depression. Hamilton was not immune from the downturn. They even lowered the retail prices of their watches to accommodate the times.

Still, Hamilton proved its resiliency.

|

|

|||||

|

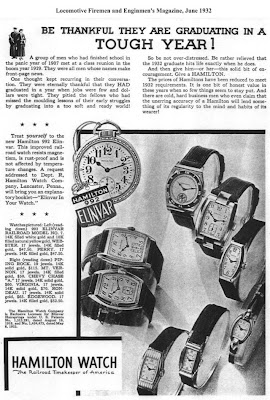

You might find some irony in the advertisement to your right. The folks in Lancaster were not hiring graduates or anyone else for that matter. They were laying people off.

A group of men who had finished school in the panic year of 1907 met at a class reunion in the boom year of 1929. They were all men whose names make front-page news.

One thought kept recurring in their conversation. They were eternally thankful that they had graduated in a year when jobs were few and dollars tight. They pitied the fellows who missed the moulding lessons of their early struggles by graduating into a too soft and ready world!

So be not over-distressed. Be rather relieved that the 1932 graduate hits life exactly when he does.

And then give him or her this solid bit of encouragement. Give a Hamilton.

The prices of Hamiltons have been reduced to meet 1932 requirements. It is one bit of honest value in these years when so few things seem to stay put. And there are cold hard business men who even claim that unerring accuracy of a Hamilton will lend something of its regularity to the mind and habits of its wearer.

Watches pictured in the advertisement were

Left side of the ad:

Elvinar 992 Railroad Model Number 7

Webster

Perry

Right side of the ad:

Piping Rock

Mt. Vernon

Chevy Chase A

Virginia

Rondeau

Edgewood

What can we take from Hamilton’s year? I would like to know if the company showed a loss because of a write down in the closing of the Illinois Watch Company. We view that today as an extraordinary, non-recurring loss. Since Hamilton showed one operating loss in 70 years, one would tend to believe shuttering the Illinois factory caused a loss.

Another question to consider: How did Hamilton make it through the depression? Let’s look at that a little deeper.

Business fail for a small number of reasons:

- Lack of experience

- Insufficient Capital

- Competition

- Poor inventory control

- Low sales

- Inability to adapt and improvise in changing market conditions

Experience

Let’s look at the Hamilton DNA starting in 1932. First, Hamilton belonged in the railroad cottage industry. Compared to the size of the railroads, Hamilton played a major and interesting role. The company emerged during the Gilded Age, a period of unprecedented growth in the United States. Railroads were the major industry, but the American Manufacturing System, mining, and labor unions also increased in importance.

In 1869, a conglomerate of railroad companies completed the first transcontinental railroad. This opened up the far-west mining and ranching regions. Travel from New York to San Francisco now took six days instead of six months .

Railroad track mileage tripled between 1860 and 1880, doubled again by 1920 and linked isolated areas with markets that allowed commercial farming, ranching and mining to form a national marketplace. American steel production dwarfed Britain, Germany, and France.

The evolution of management systems were a response to run large-scale railroad operations. Operations did not occur in a single place, but rather over widely dispersed areas Railroads faced problems of how to develop responsibility on the part of those engaged in operating different arms of the system.

The number of Pennsylvania Railroad employees in 1891, exceeded the number of personnel of the United States Army, Navy, and Marines combined.

Where did this put Hamilton? Hamilton landed in the middle of the management revolution. The company’s watch production had to fit the railroad system and from that they learned to manage. One could also argue that Hamilton put its stamp on the railroad’s management system.

Capital

In 1929, Hamilton enjoyed 31% return on sales and showed a profit of $1.8 million after taxes on sales of $5.8 million. Hamilton accumulated capital from earnings.They didn’t barrow money. When it came time to buy Illinois Watch Company, Hamilton executives wrote a check for $5 million. In 2013 money that’s $67 million. Let’ s just say, the company could survive for a number of years.

Competition

Two considerations exist. Hamilton bought defunct watch companies and specialized components. For example, between 1927-1931, the company bought E. Howard & Company. In 1920, Nobel Prize winner Dr. Charles E. Guillaume developed the elastic, resisted rust and compensated for variation in temperature. Hamilton obtained the rights to it in 1931. Hamilton’s main competitors posted losses. Waltham had loses from 1931-1934. Elgin and Bulova had losses from 1931 to 1933.

Hamilton owned 56% of the railroad market. It’s difficult to say if increased production would have meant more market share. Still the company operated at full capacity. Hamilton’s footprint left 44% of the market to a dozen or more companies over which to compete.

Inventory control

The nature of Hamilton’s business lent itself to slower cycles of production. As revenue from watches slowed, the company went into the parts business. The Lancaster based company produced superior watch parts to their Swiss rivals and sold them at lower prices.

Low Sales

The Hamilton endured sales drops in 1903 and 1931. To compensate for those years, the company altered its product mix and went into other markets. In 1918 Hamilton became the official timekeepers

for the U.S. Airmail flights between Washington D.C., Philadelphia and New York. Admiral Richard E. Byrd used a Hamilton a Hamilton watch for his highly publicized flight over the North Pole. Hamilton furnished torpedo boat watches for the first air flights from California to Hawaii and in 1928 became the “Official Timepieces” of the first Byrd Antarctic Expedition and the University of Michigan’s second Greenland Expedition.

Finally, what does the above say about Hamilton’s 1932?

Ability to adapt and improvise in changing market conditions

First, let’s just say management proved their ability to survive. Do we consider it an accident? I think not. They found ways to keep the doors open by adapting to market conditions and finding niche opportunities. They began liquidating their existing inventory and turned it into cash, whether or not they sold their products at a loss. Why?

Cash is your friend. Watches sitting in boxes can’t pay salaries, rent, property taxes, advertising or salesmen. Take another look at Hamilton’s advertisement above. You will see Piping Rock, Chevy Chase A( ladies), Virginia (also a ladies), Rondeau and Edgewood watches.

In the ad it also states, The prices of Hamiltons have been reduced to meet 1932 requirements. It is one bit of honest value in these years when so few things seem to stay put.

Final Impression

Hamilton made fine watches and never compromised. They didn’t use cheap cases or parts. They only made 17 jewel movements and above. They ran with uncanny accuracy.

They had fine management that kept the ship steady.

You gotta love them.

Copyright 2006-2017 | All Rights Reserved